Much ado has recently been made about the National Credit Union Administration’s proposed risk-based capital rules. The issue is very confusing, as many government regulations are. It also appears to be a knee-jerk reaction to the troubles from the financial crisis. This crisis did not seem to impact credit unions as severely as some of the “too big to fail” banks.

The question is, how will these proposed changes impact the credit unions’ ability to lend? If there is a change in the amount of lending, how will it impact businesses and consumers? What will be the impact on the economy as a whole? What will happen to the long-term financial stability of the industry?

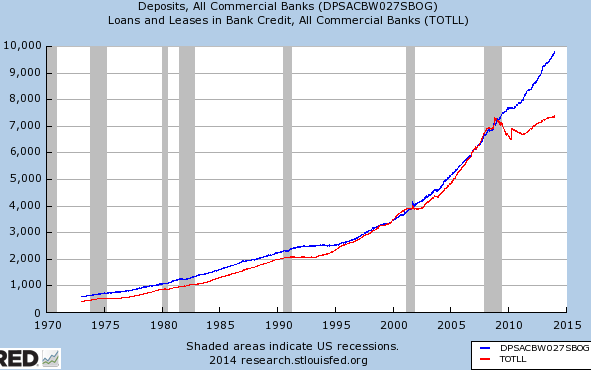

In my last blog post, Did Someone Forget to Tell Lenders the US is in a Recovery?, posted on March 30, 2014, I outlined a rather weird issue that we now face in our economy. The Commerce Department has reported 11 straight quarters of economic growth in US GDP. Yet the loan-to-deposit ratio is hitting record lows. There is currently a gap of $2.4 trillion between the amounts of deposits to the amount of loans held by banks. Interestingly, this amount is close to the additional reserves banks are leaving with the Fed.

This divergence is not normal. What we have seen time after time in our economy is, as we see growth and expect future growth, lenders will lend money to individuals and businesses to grow and expand. Capital is needed to fuel consumer purchases, which provides sales to companies. Companies also need capital to expand their operations, which in turn, will provide more jobs for individuals.

Yet today, we see the loan to deposit ratio and the labor participation rate at lows we have not seen since the economic malaise of the Carter Administration. This economic recovery has not been the rising tide that has pushed all boats higher, as many are left by the wayside.

Now, it is true that some of the lackluster loan demand has come from borrowers who are not wanting to go into more debt because of an uncertain economic future. But another large factor is lenders are not willing to lend as much due to uncertainty in their regulatory and economic future. Why would we see $2.4 trillion kept as excess reserves with the Fed? Bankers can enjoy their 0.25% return on risk-free money.

Economics 101 teaches us that increasing the minimum reserve requirements is a monetary policy available to the Fed to help slow down the economy. The new risk-based capital rules would require many credit unions to keep more money in reserves and thus have less money to lend out to members and member-businesses. So these rules will negatively impact the credit unions’ ability to lend. It will also create competitive disadvantages between credit unions and banks as the proposed capital requirements for credit unions are more stringent than those imposed upon banks.

The second question is how will the decreased lending impact consumers and businesses? While a good case can be made that less leverage is good for a person or an entity, strategic leveraging is necessary for economic growth. If one wishes to see an example of out-of-control borrowing, they need to look no further than our own US Government’s $17+ trillion debt. So, some businesses will not be able to borrow to acquire that new piece of machinery, move to a new location or even begin to start up, as lending requirements tighten due to increased capital requirements. This will lead to less jobs and less demand for goods and services.

This will impact the credit union members even more, whether the credit union is involved in business lending or not. What happens to your credit union if your primary employer in town downsizes due to lack of demand for their product? What impact would this have on your members and institution if you had multiple consumer loans go on your watch list because of a lack of income from the members to satisfy debt service? One has to conclude that the rules will be a negative for the credit union lending.

On the economy as a whole, if funds are not available for consumers and the private sector to grow, then this is a method to slow down the economy. The largest segment of the economy comes from the private sector. If you make it harder on the private sector to grow, the economy will slow down. This will continue to have the loan to deposit ratio fall. If economic growth continues forward, it will continue to benefit the large and wealthy, while leaving the small behind.

So what could be the long-term impact for the credit union industry? Fewer loans. Fewer business loans as a percent of total loans. The loans that will be put on the books will tend to have a lower margin over cost of funds, as consumer loans tend to have smaller margins than business loans. Lower margin will result in lower income. Lower income also results in lower profits, and lower profits lead to less additional capital. Less additional capital leads to further lowering of possible lending, as more money must be kept in institution capital.

The impact on credit unions can be greater than the impact on banks as the proposed credit union capital is more onerous than bank capital requirements. I would counsel my banking friends to not rejoice at this point. Having our government pick winners and losers in such a way that benefits you, will someday result in you ending out on the short end of the stick. Besides, both banks and credit unions could get further ahead if they would focus on common issues that impact both of them, such as increased regulatory items with Dodd-Frank.

I am not an advocate for poorly executed lending or undercapitalized institutions. Credit Unions need to be smart in how they operate. Capital requirements that place the CU at a competitive disadvantage to the bank is not fair. These increased requirements will also slow down vital funds needed in our communities and our economy as a whole.